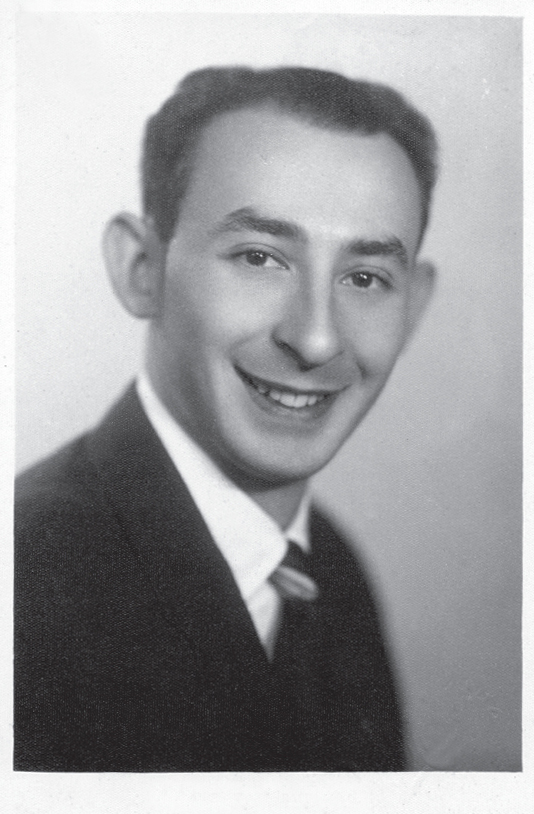

Aleksander Henryk Laks was born on 2nd August 1926 in Łódź. He was the only child of Jakub and Syma Laks. When the ghetto in Łódź was established, he was sent there with his family and remained there for four years, until it was closed in 1944. Later, he was transported with his father to Auschwitz concentration camp. Aleksander Laks survived the death march from the Gross Rosen Camp to Flossenbürg. Aleksander Laks was the sole survivor from a Polish family of over 60 people.

After the end of the war, he lived for two years in Frankfurt, in a displaced persons camp. In 1947 he left Europe for United States. Year later he came to Brazil, where his father’s sister had been living since the beginning of 1930s. He started working there as a furrier, and then as a seller. He married a Brazilian and had two sons.

In Brazil Aleksander Laks was the president of Sherit HaPleitá, a Brazilian association of Jews who survived the Nazi oppression. He wrote two books with his reminiscence from labour camps.

Aleksander Laks died on 21st July 2015 in Rio de Janeiro.

Interview by Aleksandra Pluta on 4th May 2015 in Rio de Janeiro.

Aleksandra Pluta: Did you only speak Polish at your home?

Yes, we did.

You didn’t speak Yiddish?

No, we didn’t. When my parents wanted me not to understand them, they spoke a little Jewish.

Do you speak Yiddish?

Yes, I do.

But you have learnt it here, in Brazil, right?

No, in the ghetto.

You learnt it in the ghetto. At your home your parents didn’t…

They spoke Polish.

I suppose they wanted to protect you in some way.

They didn’t want to protect me. We spoke Polish because I was in Poland, we were Poles, we spoke Polish. In the ghetto I learned to speak German and Jewish. In the USA I spoke English. Here I speak Portuguese. Five languages.

At first, they let me attend school. I was 11–12 years old so I went to school. One day they said that everyone has to attend school. Everyone who was absent that day [unintelligible] and goes to school. I came home, I told my father what they wanted. “Father, I won’t go to school.” “Don’t go to school.” He hid me at my mother’s, she was still alive back then. Murdered. I didn’t go to school. The entire school, not just the class. The entire school, the entire school was transported to… Chełmno. I am the only survivor of that school.

Aleksandra Pluta: It was a special operation to transport all those children to Chełmno, wasn’t it?

That’s true. I am the only one who didn’t go to school.

I have some good and some bad memories. Antisemitism in Poland was very strong. And Poles always said that Jews killed Christ and they all knew about it and wrote on the fences: Down with Jews, Jews back to Palestine, Jews cockroaches. I saw it. I was a child and I loved Poland. It was my homeland. I didn’t have any other. They didn’t want me. I loved Poland a lot. At home as well. My parents spoke Polish, I spoke Polish. But I was a good student at school, doing not too bad. It was OK. [unintelligible] – I can’t say I had. I was a Jew. I loved Poland. This is why. In 1939 Germans invaded Poland and after several weeks or even sooner they entered. Just in Łódź there were a lot of Germans and they started establishing the ghetto. I was in the ghetto and it hurts me a lot. When we came to the ghetto, Christians, Poles. I was also a Pole. They said: “Jew, throw down your coat. Throw me your coat. You’ll die anyway. And your shoes.” My friends. This hurts me till this day. And still… I haven’t forgotten, I haven’ spoken Polish for 50 years. And I still speak Polish.

Aleksandra Pluta: How long were you in the Łódź Ghetto?

4 years. Always worse and worse. Always worse. I worked after school, no I worked at the hardware, [unintelligible]. At first I worked at the central, central hardware. Then [unintelligible].

It was a hardware factory. What did it produce?

Everything. Plates, everything. Everything.

What did the factories produce?

Factories produced everything, also everything. Even straw, they also had straw shoes. Clothes, those eagles. It all was made in the ghetto. Tenants.

I remember I had friends. It didn’t matter for me whether someone was a Jew or a Catholic. I had lots of friends. Maybe not a lot, I was a child, I was a child back then. I was 15 when it all started. I went to the ghetto. And it was really bad in the ghetto. There was no food to be had, I worked, I worked like adults. Can they catch me and send me away? My father and my mother worked in the ghetto. That was all. One day at a time.

Aleksandra Pluta: Where did your mother work? And your father?

My father worked in the butchery, there was a butchery, you see. And my mother worked in the straw shoes factory.

In a factory producing straw shoes?

Yes.

And the butchery, who was it for? Was the butchery used by the ghetto residents?

For the ghetto residents. Sometimes they made there… and sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes cold meat.

Aleksandra Pluta: Do you have any siblings?

I have no one.

Did you have any siblings?

Yes, I had, 60 people.

It was your entire family.

Entire family. 60 people.

How many brothers?

No brothers. I have no one. I am the sole survivor of a 60 people family.

You stayed there until its liquidation in 1944?

Yes.

In the ghetto.

In the ghetto.

And then?

I came to Auschwitz. In Auschwitz they took my mother, they took her to the crematorium. I was with my father in Birkenau for some time and I was sold to Gross Rosen, now in Poland. But back there it was Germany.

What do you mean “sold”?

Sold as a labourer.

It was a labour camp? It wasn’t a concentration camp, right?

There was a concentration camp. But it wasn't Gross Rosen. I was at a labour camp. We erected fortifications for the German army against the Russians, right? I stayed there for some time and they took me to the death march. Todesmarsche.

Aleksandra Pluta: You spent the winter or the summer in Auschwitz?

We were there during Christmas. Before that the camp commandant said that for Christmas, if we keep up the good work, we can get one more portion of soup. We were always looking forward to Christmas. But when Christmas came, we came to the camp, got back to the camp, and then all of us were sent to the barracks. They suddenly started to beat us up that… [unintelligible]. Some people took the wrong one, that we went to the barracks, we took…

Coats.

Coats. Some didn’t bring any coats. They left us and then a man came, the one who said we were going to get soup. He was really drunk. And said that "You didn’t work well, you killed Christ. Because you killed Christ". And he left us. He left and we stood for a long time. Many of us died. We saw that those men from SS sang and we stood there in the snow. Some of us dies. Some time later one of SS came, saw a lot of dead. He ordered us to go back to the barracks. It was the last Christmas I attended.

Todesmärsche. Death marches. 2 million Jews died. We walked into the snow, we slept on the snow, at night we got, we got 4 or 5 potatoes. One who get out of the line - killed. One who...

Did somebody lean on another man?

When somebody leaned on another man, he was shot. Those who couldn’t walk were shot. When someone had some snow to drink, just some snow, he was shot. At night they sometimes told us to make a fire so we held our pyjamas and people in pyjamas went into the fire. And they shot. They liked it. And we fell ill with pneumonia, etc. In the morning there was just a half of us left. They just shot, shot and shot.

And that was where?

In German territory. We walked from Gross Rosen to Flossenbürg. When we set off there were 80 of us, when we reached our destination, only… were left.

10?

No, no. 100.

And when you set off there were 800 of you…

Less than 100.

Why did you survive? Was it the fact that you were young, strong?

No, I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know the reason. I know why I survived. To be and to say to everyone that it cannot happen again. Never. With no one. I survived, why, God knows, I don’t.

Death marches, were there a lot of them or just the famous one that you were telling us about, with 800 people?

Everywhere, everywhere. Only in winter.

In winter.

In winter.

How long did this death march took?

A month, maybe a little more or less.

And you stayed with your father the whole time?

Always. This is why I survived. I survived thanks to my father.

After 2 years you spent in Germany in a camp for…

Displaced persons.

How were you allowed to get to the US? Was it possible with the help of IRO?

No, I was living in the camp. When they wanted no more camps they said that who wants to stay in Germany or Holland, can be expelled. I didn’t want to stay in Europe anymore, I wanted to leave. I could go to the US, to Canada and to Australia. I chose the US. I stayed there for a while and then I went to Brazil.

How did you travel from Germany to the US?

I went there on a ship. 9 days. I didn’t eat anything for 7 days. I couldn’t eat.

But not that they didn’t give you any food on the ship but because you felt ill?

I just couldn’t.

Did you suffer from sea sickness?

Yes, I did.

But the ship…

It was a transporter for the American army.

So it wasn’t a passenger vessel?

It was a passenger vessel but previously it had been for soldiers.

What did you take with you to the US? Did you have any possessions? Did you take anything with you? Did you have any luggage when you left for America?

I did. A shirt. One shirt.

And the documents, any means to survive?

I have my documents here. UNRRA - United Nations Relief and Rescue. I have them here. Only this. But I had another one, written like that. And this is what I had when I came to the US. There was the United Service for New Americans. Service for new Americans. They gave us food. We were at a hotel for 3 or 4 days. And then I went to work. I worked as a furrier.

Did you stay there long?

Almost a year.

Aleksandra Pluta: So you came to Brazil in 1949 or 1950?

No, in 1948.

And you stayed in Ilha das Flores?

No, no. I came as a tourist. And my family, my aunt and uncle paid so I could stay here. I came here only for 30 days. They paid there so I could stay. And I did, I didn’t come back.