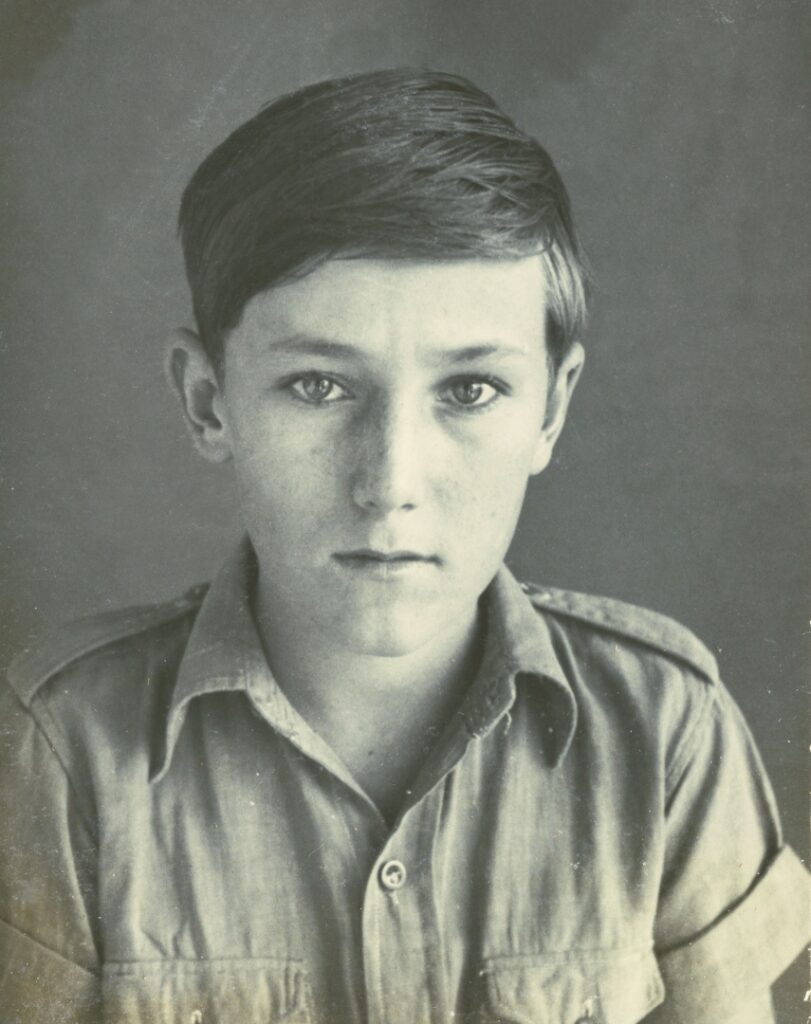

Jerzy Tomaszek was born on 6th January 1928 in Stanisławów near Lviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine). His father, Stanisław Tomaszek, was a doctor and a renowned social activist. After the invasion of the Red Army on Poland he was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in a labour camp as a counter-revolutionist. Several months later Jerzy Tomaszek and his sister, Iwona Świętochowska, their mother and grandmother were transported deep into the Soviet Union. They lived and worked in the kolkhozes in Pieszczanka and Presnogorkowka.

After the announcement on signing the Sikorski-Mayski agreement Jerzy’s mother, Zofia, decided to escape from her exile. After having reached Turkmenistan with her children, she decided to temporarily leave her children at the orphanage so that they could safely survive the war turmoil. In the meanwhile, she worked as a medical assistant at the front. The siblings, after having crossed the deserts of Iran and the harbours of Iraq, found shelter in India in a settlement for Polish orphans built by Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijaysinhji in Balachadi. After several months of being apart, her mother joined them. Soon later the Tomaszek family moved to a refugee camps in Africa in Kondoa, Kidugali and Tangier. They returned to Poland in 1947 and settled in Bytom.

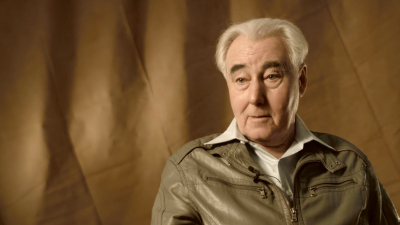

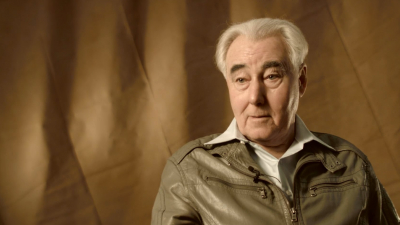

Jerzy Tomaszek graduated from the Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice. He designed laboratory facilities for the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, the Szczecin University of Technology and the Carbon Chemistry Institute in Zabrze. He was a member of the “Solidarity” and a councilman in Bytom.

He was awarded the Silver Cross of Merit and the Medal of the 40th Anniversary of People’s Poland.

Interviewed by Olga Blumczyńska in December 2014 in Warsaw.

A miracle en route East

It was of course a full train of freight wagons... how many there were, I can’t say, and still it needs to be said that it was a transport on 13 April 1940 and of course we later learned that this transport was for the families of the people who were murdered in Katyn and families of the arrested. And since my dad was arrested, then as his family, we also found ourselves on the transport. There were around forty people in each wagon. I don’t recall us ever being hungry during the transport, but there was very little to drink. Because, they sometimes provided a bucket of water per wagon, and sometimes not. It varied. For example, we had a situation along the way, my grandmother had a heart illness, she needed her medication and we didn’t have a drop of water to wash it down. There was a physician assigned to the transport and we started calling for them in Russian through the windows “vrač” and well she came in, my mom tells her that grandma is sick and needs to take her medicine, but we don’t have any water. And the physician said “ask God to give you some”. And she left. And lo and behold, not 15 minutes later, it started to rain and we caught some water in a cup and grandma could wash down her medicine. Whether it was God, it’s hard to say, or just a coincidence. Anyway, the doctor must’ve felt stupid when she saw that it started to rain, because she could see that we were, through that window, everybody could, because the windows were barred and you could fit a cup through them.

It was of course a full train of freight wagons... how many there were, I can’t say, and still it needs to be said that it was a transport on 13 April 1940 and of course we later learned that this transport was for the families of the people who were murdered in Katyn and families of the arrested. And since my dad was arrested, then as his family, we also found ourselves on the transport. There were around forty people in each wagon. I don’t recall us ever being hungry during the transport, but there was very little to drink. Because, they sometimes provided a bucket of water per wagon, and sometimes not. It varied. For example, we had a situation along the way, my grandmother had a heart illness, she needed her medication and we didn’t have a drop of water to wash it down. There was a physician assigned to the transport and we started calling for them in Russian through the windows “vrač” and well she came in, my mom tells her that grandma is sick and needs to take her medicine, but we don’t have any water. And the physician said “ask God to give you some”. And she left. And lo and behold, not 15 minutes later, it started to rain and we caught some water in a cup and grandma could wash down her medicine. Whether it was God, it’s hard to say, or just a coincidence. Anyway, the doctor must’ve felt stupid when she saw that it started to rain, because she could see that we were, through that window, everybody could, because the windows were barred and you could fit a cup through them.

Father's death on the way to the labor camp

My father wasn’t only a doctor, he was a well-known social activist in Stanisławów. And he was active in sports, as he was one of the founders of the skiing society. Even when the Camp of National Unity was created my father was propositioned to run for the Sejm from their ballot, but he wasn’t too big on the idea and refused, so he didn’t get a career in politics, but he was known as a social activist. But the second story which was probably even more... contributed to his arrest. During the Great War, father was stationed at the Przemyśl Fortress and when the Austrians gave it up in 1915, he was taken prisoner by the Russians along with the rest of the garrison and transported to Siberia, and there, somewhere around Omsk, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, he spent 7 years. He returned with the last transport in 1922, but later in Poland, he stated all of that in his biography, because his original biography survived, where all of this is detailed. It was a clear counter revolution and the investigators or dad himself said during the inquiry or they found the biography and it was the reason to sentence him to 10 years. Of course, as is usually the case with the Soviets, there wasn’t any court case, administrative proceedings, 10 years of hard labour, which as it turned out later was not to be the case, as dad didn’t make it to the camp at all. He died in the transport on the way there. Father died on 30 November 1941, it was, I think, four months after signing the Sikorski-Majski agreement where they undertook to free all prisoners, and when they did, that dad died in prison, around four years after... four months after signing this act.

My father wasn’t only a doctor, he was a well-known social activist in Stanisławów. And he was active in sports, as he was one of the founders of the skiing society. Even when the Camp of National Unity was created my father was propositioned to run for the Sejm from their ballot, but he wasn’t too big on the idea and refused, so he didn’t get a career in politics, but he was known as a social activist. But the second story which was probably even more... contributed to his arrest. During the Great War, father was stationed at the Przemyśl Fortress and when the Austrians gave it up in 1915, he was taken prisoner by the Russians along with the rest of the garrison and transported to Siberia, and there, somewhere around Omsk, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, he spent 7 years. He returned with the last transport in 1922, but later in Poland, he stated all of that in his biography, because his original biography survived, where all of this is detailed. It was a clear counter revolution and the investigators or dad himself said during the inquiry or they found the biography and it was the reason to sentence him to 10 years. Of course, as is usually the case with the Soviets, there wasn’t any court case, administrative proceedings, 10 years of hard labour, which as it turned out later was not to be the case, as dad didn’t make it to the camp at all. He died in the transport on the way there. Father died on 30 November 1941, it was, I think, four months after signing the Sikorski-Majski agreement where they undertook to free all prisoners, and when they did, that dad died in prison, around four years after... four months after signing this act.

Baptism in freight wagon

There was this Boguś, but when we the ladies talked, it turned out the Boguś wasn’t baptised. So the ladies raised a commotion and baptised him using the water. And since I was the oldest man, because it was... there had to be a lot, because it were generally women and children, I was the oldest male there, so I became the godfather.

There was this Boguś, but when we the ladies talked, it turned out the Boguś wasn’t baptised. So the ladies raised a commotion and baptised him using the water. And since I was the oldest man, because it was... there had to be a lot, because it were generally women and children, I was the oldest male there, so I became the godfather.

Everyday life in kolkhoz

We were transported a bit further to this village called Pieszczanka, they offloaded us in front of the Folk House, they told us we could sleep there, and next day when we woke up this NKVD guy came along and said “go look for apartments”, the arrivals were, well you can see the Polish group from Pieszczanka, there were, I don’t know maybe eight families, so there wasn’t any sort of living barracks, nothing. The NKVD comrade said “you were penally displaced, you’re not worthy to work at a Soviet kolkhoz”. And there are women and children here, so there’s a general question of what are these people supposed to do for a living since they can’t work at the kolkhoz, and there isn’t any other work, there was nothing there. How many people were living in that village, I couldn’t tell you, around a hundred I’d say. There was this Folk House, a ruined orthodox church thoroughly destroyed during the revolution and one village store, where they sometimes brought in some goods. Well, my mom found us some quarters, we moved in, how long we lived there, because in Pieszczanka... we moved around a lot. My mom was the only one from that Polish group to immediately strike a deal with some of the women, where someone had a piece of land they didn’t cultivate, and we dug through it by hand in a couple of weeks, of course with borrowed equipment, planted some vegetables, sowed, I don’t know where she got them, probably bought from the Russian women. So we were the only ones to have, when it all grew, our own veggies, and there was this post office, where the letters arrived, daily I think the postman arrived, will there be a package from Poland or not. There wasn’t any limitation on packages. We also received packages from our family in Lviv, and doctor Gut sent cash. That could be sent too, so it was undoubtedly helpful. Mom never learned dressmaking, but she was manually inclined, so she started to sew for the other women at the kolkhoz who didn’t know how. The family in Lviv sent us a sewing machine, hand operated with a crank, and it prospered, but a couple months later the NKVD guy came back and said that we couldn’t do that unless we paid a tax. And when gave us the calculation, it turned out we would have to add to the business, and so mom suspended the activity, and only continued in secret for good friends. Anyway, she was able to earn some money that way. She had tremendous initiative from the very beginning, so we survived and we have my mom to thank for that, and she was from a rich family, we were... part of the affluent group of society in Stanisławów.

We were transported a bit further to this village called Pieszczanka, they offloaded us in front of the Folk House, they told us we could sleep there, and next day when we woke up this NKVD guy came along and said “go look for apartments”, the arrivals were, well you can see the Polish group from Pieszczanka, there were, I don’t know maybe eight families, so there wasn’t any sort of living barracks, nothing. The NKVD comrade said “you were penally displaced, you’re not worthy to work at a Soviet kolkhoz”. And there are women and children here, so there’s a general question of what are these people supposed to do for a living since they can’t work at the kolkhoz, and there isn’t any other work, there was nothing there. How many people were living in that village, I couldn’t tell you, around a hundred I’d say. There was this Folk House, a ruined orthodox church thoroughly destroyed during the revolution and one village store, where they sometimes brought in some goods. Well, my mom found us some quarters, we moved in, how long we lived there, because in Pieszczanka... we moved around a lot. My mom was the only one from that Polish group to immediately strike a deal with some of the women, where someone had a piece of land they didn’t cultivate, and we dug through it by hand in a couple of weeks, of course with borrowed equipment, planted some vegetables, sowed, I don’t know where she got them, probably bought from the Russian women. So we were the only ones to have, when it all grew, our own veggies, and there was this post office, where the letters arrived, daily I think the postman arrived, will there be a package from Poland or not. There wasn’t any limitation on packages. We also received packages from our family in Lviv, and doctor Gut sent cash. That could be sent too, so it was undoubtedly helpful. Mom never learned dressmaking, but she was manually inclined, so she started to sew for the other women at the kolkhoz who didn’t know how. The family in Lviv sent us a sewing machine, hand operated with a crank, and it prospered, but a couple months later the NKVD guy came back and said that we couldn’t do that unless we paid a tax. And when gave us the calculation, it turned out we would have to add to the business, and so mom suspended the activity, and only continued in secret for good friends. Anyway, she was able to earn some money that way. She had tremendous initiative from the very beginning, so we survived and we have my mom to thank for that, and she was from a rich family, we were... part of the affluent group of society in Stanisławów.

Escaping the USSR

The element of that decision was, I think that everything was hopeless, ‘cause there was nothing, we don’t go to school, no perspectives, well anyway, we decided in November ‘41 to leave that place. It looked like this, that at night, this truck driver we paid off arrived. He was transporting some goods to Kostanay and he prepared this hiding place between the sacks, and we hid with our things in there, and he arrived after dark of course, and we rode throughout the night to oblast, that means Kostanay, but he must’ve been informed, because he dropped us off in front of the Polish delegation. So, we received our departure documents, even a small amount of money to pay our way, and we travelled from there, on our own this time, to Uzbekistan. And so we camped at the station, so I learned what it’s like to be homeless, because we didn’t have a place of our own, every couple of hours, they would expel everyone from the station, and the temperatures were way below negative twenty, almost thirty, it was winter after all. Two nights stick out in my memory. We managed to get a single spot, couple of kids, me, my sister, and couple other Polish children, we moved this sort of decorative bench, it was probably stolen from a church, from the wall and moved into that space and stood there, you could lean on the wall and that’s how we spent the night. The second night I remember was when I slept on a windowsill but the window only had a single plate of glass, so I froze to the glass, in the morning, I couldn’t do anything, they had to tear me away from it. Other nights, I don’t remember. I remember some Russian lady who was lying down, she had a terrible case of lice, they were all around her. And because of that, she had some space around her, because everyone... had lice, we caught them as early as the transport from Poland, so one of the families had to have them, so only after we made it to the kolkhoz, we managed to get rid of them. On the other hand, we didn’t manage to get rid of the bedbugs, they bit us viciously all that time.

The element of that decision was, I think that everything was hopeless, ‘cause there was nothing, we don’t go to school, no perspectives, well anyway, we decided in November ‘41 to leave that place. It looked like this, that at night, this truck driver we paid off arrived. He was transporting some goods to Kostanay and he prepared this hiding place between the sacks, and we hid with our things in there, and he arrived after dark of course, and we rode throughout the night to oblast, that means Kostanay, but he must’ve been informed, because he dropped us off in front of the Polish delegation. So, we received our departure documents, even a small amount of money to pay our way, and we travelled from there, on our own this time, to Uzbekistan. And so we camped at the station, so I learned what it’s like to be homeless, because we didn’t have a place of our own, every couple of hours, they would expel everyone from the station, and the temperatures were way below negative twenty, almost thirty, it was winter after all. Two nights stick out in my memory. We managed to get a single spot, couple of kids, me, my sister, and couple other Polish children, we moved this sort of decorative bench, it was probably stolen from a church, from the wall and moved into that space and stood there, you could lean on the wall and that’s how we spent the night. The second night I remember was when I slept on a windowsill but the window only had a single plate of glass, so I froze to the glass, in the morning, I couldn’t do anything, they had to tear me away from it. Other nights, I don’t remember. I remember some Russian lady who was lying down, she had a terrible case of lice, they were all around her. And because of that, she had some space around her, because everyone... had lice, we caught them as early as the transport from Poland, so one of the families had to have them, so only after we made it to the kolkhoz, we managed to get rid of them. On the other hand, we didn’t manage to get rid of the bedbugs, they bit us viciously all that time.

Polish orphanage over the Indian Ocean

It was around thirty kilometres from Balachadi, it was located directly on the coast of the Indian Ocean with the Maharajah’s summer residence close by, I think he had more of those, so from time to time they let us in there and gave us sweets for whatever occasion. And very often, we bathed in the ocean, in Jamnagar, well, there was a beautiful Maharajah’s palace and we visited a couple times, not all of us of course, but in groups, he invited the kids, but I don’t remember the place, but I do remember the Maharajah’s garage. He had a couple dozen cars there, and most intriguing for me was the one they used to ferry the women, because they had venetian glass in their windows. If you tried to look inside, all you could see was your own reflection, and from the inside, you could see everything clearly, so the plebs, when the lady is going by, the plebs couldn’t see her. Well, admittedly they weren’t Muslims, they were Hindu, but the Maharajah didn’t want his women to be stared at by just anybody. And there were at least twenty cars, maybe more, but he was a very rich Hindu prince, one of the wealthier, and he had the corpulence to prove it. He visited regularly, from time to time, he came for all the holidays, shows were put on for him, folk dances, a folk band was organised.

It was around thirty kilometres from Balachadi, it was located directly on the coast of the Indian Ocean with the Maharajah’s summer residence close by, I think he had more of those, so from time to time they let us in there and gave us sweets for whatever occasion. And very often, we bathed in the ocean, in Jamnagar, well, there was a beautiful Maharajah’s palace and we visited a couple times, not all of us of course, but in groups, he invited the kids, but I don’t remember the place, but I do remember the Maharajah’s garage. He had a couple dozen cars there, and most intriguing for me was the one they used to ferry the women, because they had venetian glass in their windows. If you tried to look inside, all you could see was your own reflection, and from the inside, you could see everything clearly, so the plebs, when the lady is going by, the plebs couldn’t see her. Well, admittedly they weren’t Muslims, they were Hindu, but the Maharajah didn’t want his women to be stared at by just anybody. And there were at least twenty cars, maybe more, but he was a very rich Hindu prince, one of the wealthier, and he had the corpulence to prove it. He visited regularly, from time to time, he came for all the holidays, shows were put on for him, folk dances, a folk band was organised.