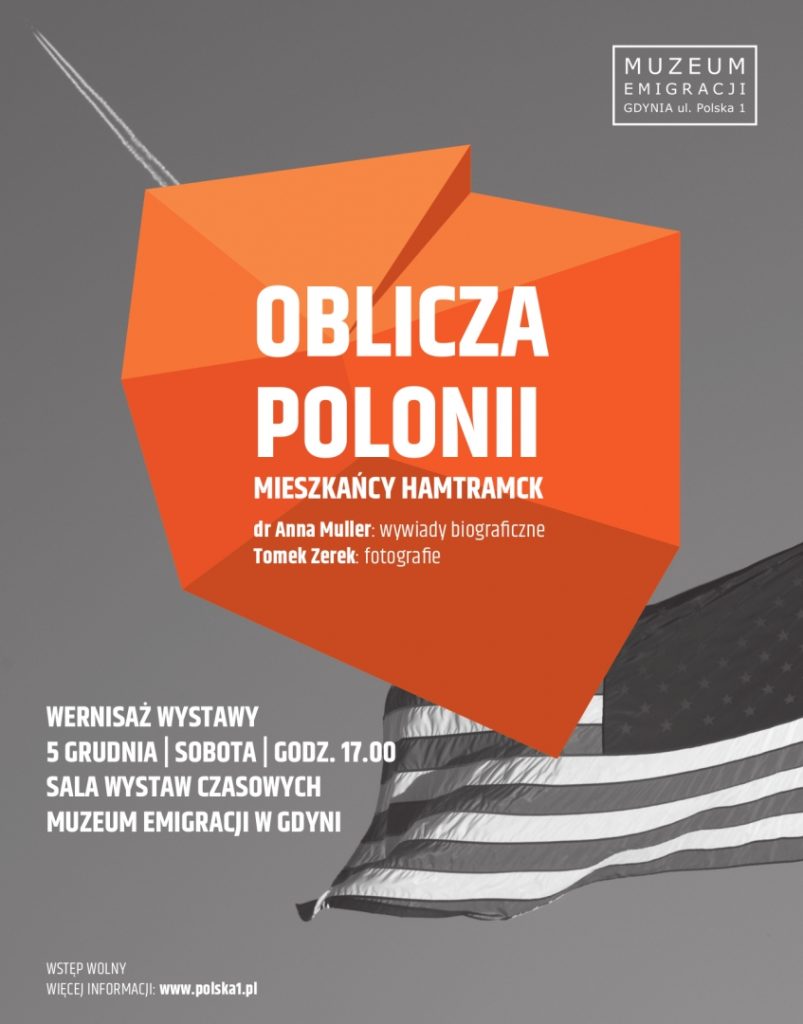

Faces of Polonia: People of Hamtramck

Hamtramck is a small town in Michigan, USA, surrounded by Detroit on all sides. Its two square miles can be traversed North to South and East to West within a single day. The town was created at the beginning of the 20th century as a settlement of German farmers. After opening a Doge factory in 1914, the area witnessed a mass Polish emigration. They arrived both from partitioned Poland, and various other areas of the United States, e.g. Pennsylvania, where they worked as miners. Thanks to them, Hamtramck saw dynamic growth over a period of 10 years, becoming an industrial town. Even as late as the 1970s., around 90% of the local inhabitants were of Polish heritage.

For many Poles, the town was the first stop in achieving the American dream. In recent years however, Hamtramck was affected by the social and economic changes that affected Detroit. The collapse of the automotive industry was for many people, an impulse to leave Motor City. Today, the nearly 3.5 thousand Polish-Americans constitute only 14.5% of the entire population. These changes are accompanied by mass emigration from other parts of the World – initially from Albania and later from Bangladesh and Yemen. Hamtramck once again plays the role of a place where various emigrant groups can start their lives in the United States.

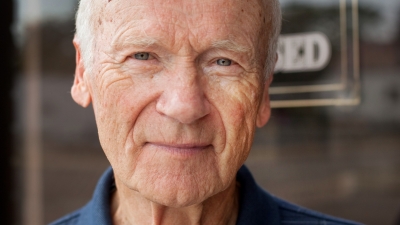

The “Faces of the Polish Diaspora – the Citizens of Hamtracmck” exhibition presents the effects of the work of researcher dr Anna Muller and photographer Tomasz Zerk, who documented the lives of the Polish-Americans of Hamtramck. The project is comprised of a series of 30 biographical interviews and photographs that portray the cultural heritage of the town and its modern-day citizens.

It’s surprising how rich were the lives of the Polish Diaspora in Hamtramck. The Poles created their own theatre, dance and musical groups, a philharmonic. The town had around a dozen social and cultural Polish institutions. They experimented with new trends in American culture, attempting to find a form which would allow the town to retain its uniquely Polish character. Despite demographic changes in its social fabric, Hamtramck is still closely connected to its Polish past. Many streets bear Polish names such as Sobieski St. or Poland St. Hamtramck is home to Polish attorneys and physicians, there are also funeral houses owned by people of Polish heritage. Polish can be heard on the streets, many cars bear Polish symbols: the flag, the Polish eagle… Polish products can also be found in Bengal stores.

It is striking how much families wish to maintain Polish culture: through religion, language, and sometimes through conscious decisions to become Polish despite not knowing the language. Being a Pole in Hamtramck is a way of being American. It is an attempt of defining oneself in the huge melting pot that is the United States.

Modern-day Hamtramck is a blend of different cultures and ethnicities. The citizens communicate in 26 languages. In the last several decades, Hamtramck was dominated by Bangladeshi and Yemeni, mostly Muslims, but also Buddhists. During the day, along with church bells, one can hear calls for prayer from mosques. In November of the current year, Hamtramck became the first town in the United States with a Muslim majority in its city council.

Pahiatua

At a

time when Poles were movingto the south of the USSR and the Middle East

for long weeks, in June 1943, the USS Hermitage vessel arrived in New

Zealand in June 1943 for a while, which brought an invitation of the

government for seven hundred Polish children from Iran to Mexico. They

were then visited by the countess Maria Wodzicka, wife of the then

consul of the Republic of Poland in New Zealand, K.A. Wodzicki. Seeing

the tragedy of the toddlers, she decided to create a place where they

could live until the end of the war. This idea was also suggested by her

to the wife of the then Prime Minister of New Zealand, Janet Fraser,

who supported Maria Wodzicka in these activities. The choice of location

was simple. Polish children were to live in Pahiatua, where from 1942

there was a camp for citizens hostile to the allies of the countries. At

the end of 1943, the internees were moved to Matiu-Somes Island, and

the camp began to rebuild the barracks and houses of volunteers from

Pahiatua. The New Zealand government invited Polish children and their

guardians to New Zealand.

In the summer of 1944, a series of

lectures was organized for Polish children about the country to which

they were soon to leave. Each of them was to take to New Zealand Polish

books that they had in their possession. These collections were to

create the nucleus of the Polish library in the Pahiatua camp. The

children got small cardboard suitcases, to which they could pack the

most necessary things.

Travel

The trip to New Zealand began on September 27, 1944, when 733 children

and their 105 guardians left Isfahan by buses and lorries. The first

stop was at the military base in Sultanabad (today: Arak), where

American soldiers entertained the frightened and tired kids. After a

short stop, the children went to Ahwaz, where they spent two days. On

October 4, 1944, Polish convoys left for Chrramszachry at the mouth of

the Tigris and the Euphrates, where the children and their guardians

boarded the ship Sontay. After a six-day cruise, on October 10, 1944,

they reached Bombay. There, they moved to the USS Randall transport. On

October 15, the ship sailed from India to New Zealand. On the deck of a

military ship, Polish children and the ship’s crew played football. A

few of the balls fell over board.

In the evening of October 31,

1944, the USS Randall sailed to the shores of New Zealand. In the

morning of the next day, the ship reached the port of Wellington, the

capital of New Zealand, where it was welcomed by the orchestra and prime

minister Peter Fraser.

From Wellington, Polish children went

to Pahiatua, 160 km away. New Zealand children were released from the

lessons to welcome Poles. They waved and sang standing by the road,

which was followed by two trains with Polish children. After reaching

Pahiatua, 33 trucks transported all of them to the town located on its

southern borders, which was soon to become the Polish Children’s Camp.

„There was neither horror nor fear here”

Since the children from Pahiatua after the end of the war were to

return to Poland, the language and infrastructure of the camp were

Polish. These were also the names of barracks and alleys. The operation

of the camp was supported by the Polish government in exile (until the

Allies have recognized it … in April 1946), then the New Zealand army.

The caretakers and teachers of the children were Poles, but some of the

teachers were New Zealand teachers who taught Poles English and popular

sports in New Zealand – rugby. Small Poles spent their school holidays

frequently with New Zealand families who gave children a chance to

experience a family atmosphere in a new country.

In

the memory of the Adults of Pahiatua, the camp is described as a happy

period. Despite the drama of the war and its consequences in the world,

children could enjoy a normal, peaceful childhood with its usual

problems – a burst of homework, matches, mischief on the playground,

dances and scout meetings …

Many New Zealanders were outraged

by the help, Poles received from their country. There were voices that

some New Zealanders cannot afford such good conditions in which Polish

children lived – free accommodation, free meals and no obligation to

work. The growing reluctance meant that the New Zealand Prime Minister

had to respond to these accusations on many occasions, stressing that

the Camp benefitted from the funds of the Polish Government in London

and maintained itself thanks to the work of Polish guardians.

Closing

The conference in Yalta (February 4-11, 1945) was not without

significance for the fate of the Pahiatua camp. After the territories

from which most of the children came were incorporated into the USSR and

Poland was under Russian influence, the government of New Zealand

wanted to assimilate Polish children. There was an idea for the

guardians to give their children up for adopting families in New

Zealand. The Polish guardians objected strongly to this, it was

important to them that the children were still brought up in the spirit

of Polishness. Prime Minister Fraser was of the opinion that a difficult

decision about their future life should be left to the children

themselves. An agreement was reached between the Polish camp authorities

and the staff, the New Zealand church and the government, under which

the Polish Children’s Camp became Little Poland.

After

1948, children were sent to boarding schools. The boys were sent to the

Bursa of Polish Boys in Hawera, and the girls – to the Polish Girls’

Dormitory in Wellington. Young people who started their professional

lives lived in workers’ hotels, some of the youngest children went to

foster families. Some of the children from Pahiatua decided to stay in

New Zealand and build a new life here. Some decided to return to Poland

with the hope that they would be able to rebuild what was left there.

The Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua was officially closed on April

15, 1949.

For three years after the closure of Little Poland,

there was a camp for stateless displaced people from forced labor

centers in Germany. After its closure in 1952, the area became a farm,

where the only trace of the former Polish Children’s Camp functioning

here was a grotto with a statue of the Virgin Mary.

The

book „Two homelands” tells the story of Children from Pahiatua and the

fate of the camp. It is the result of the work of the Children of

Pahiatua: Stanisław Manterys, Adam Manterys, Halina Manterys, Stefania

Zawada and Józef Zawada.

Upload: HERE (in Polish)

Fragments of interviews are part of a full-length documentary film about the fates of Children of Pahiatua „Deceit destiny” directed by Marek Lechowicz.