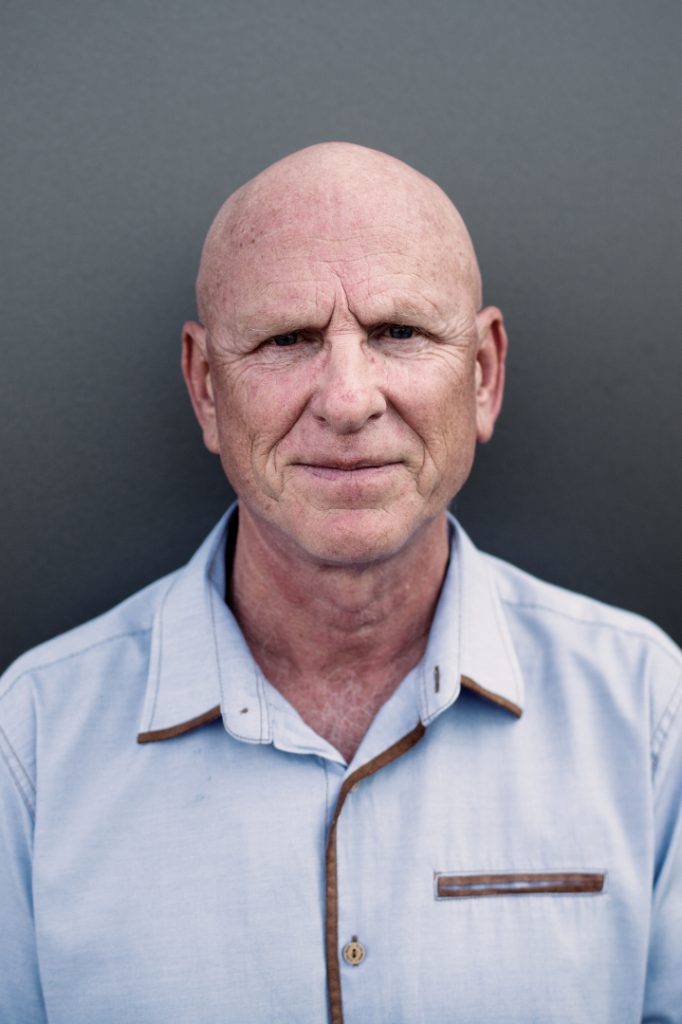

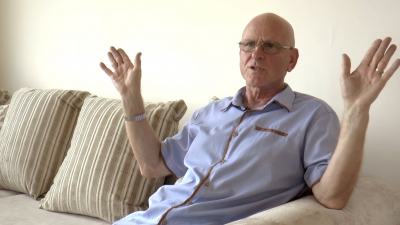

Konstanty Bilewicz was born on 10th October 1948 in Usedom. His father, Juliusz Bilewicz, was a Deep-Sea Captain and the first river pilot in the Oder; he also was the port captain in Ustka. Konstanty Bilewicz graduated from the Polish Naval School as a radio officer.

In 1973 he decided to leave Poland. He was the subject of painful repressions due to his origin and participation in the events of December 1970 in Gdynia. After several failed attempts he managed to get on board of TSS Stefan Batory and reach Copenhagen. From there he went by a ferry to Malmö, where he asked for asylum. However, he did not stay in Sweden. After some time he decided to join his brother living in Australia. This trip marked the next stage of Konstanty Bilewicz’s professional life. He worked as a jet engine mechanic and later served at a polar station on the Macquarie Island.

In Australia he started a family and he has two daughters. Currently, he lives in Perth.

He was interviewed by Olga Blumczyńska in July, 2014 in Gdynia

I tried to escape every day, every day I went to the port, every day in Gdynia and Gdańsk and I watched, where to escape, how to escape. My next attempt was to swim to the bay, climb up the mooring line, the anchor, on the anchoring chained to a foreign vessel, swim out to a port, as blinded, hide somewhere so that nobody would do a search on me and then peacefully set off. And so I swim. Night. Cold water. I reach a ship. Second chain, slippery with grease, no chance. I had to swim back. It’s much harder to swim back than towards the ship. And I can give you one last example. Some Swedes were swimming into the yacht marina in Gdynia. So one day I had a chat with a Swede. I observed him as he went to a café. I followed him. The Polish Border Guard was standing near the foreign yachts. Everywhere where there was a foreign yacht or ship there was always the Polish Border Guard. They were keeping the society in a cage, they didn’t let us leave, so there was no chance to do so. I had a chat with that Swede and we agreed that at a certain time he will set off, throw a line with a knot overboard, so that I could grab it and he wouldn’t have to stop and just swim next to a buoy and I’ll catch it. When we swim outside territorial waters I will come up (unintelligible) and he will drop me off, not on Bornholm even but somewhere near so I could swim there myself. So I swam but he didn’t show. And I had to swim back again. This happened practically every single day, and every day my life was to put something on me, eat something and just keep looking a way to escape.

Batory, before it sailed off, was fenced, with a guard booth to the quay. You couldn’t get under Batory from the quayside because of the guard and the access from the Maritime Railway Station was also impossible because of the Polish Border Guards and one had to have a pass to do so. And so I went around and I had no chance there so I started coming back and on the steps, at the very top of the steps there was a group of young officers from the marine school, first year students who were to sign on Batory for their training cruise. The vessel was sailing from Gdynia do Copenhagen, its first stop, then London and to the U.S. across the Atlantic. Just as I was leaving somebody shouted “Bill”. That was my nickname used by all my friends. So I look back. I hear somebody from the group repeating my name, Bill. I had a friend in the marine school. His name was Oleś, maybe I’ll leave out his last name. His brother was studying there and he knew me well. So he called me. I walked up to them and they surrounded me, all happy, and asked whether I worked at Batory. I have no idea why I said yes. Now, if somebody asked me why, I couldn’t tell because I simply don’t know why. Yes. So they were really enthusiastic. We no longer feel alone. Can you walk us around, show us everything? At that moment a thought occurred to me. What’s going happen if I get them on board? I have a black briefcase. But their documents are important. I didn’t have any documents myself. No passes allowing me to enter... So the boys started telling me that the communist who is going to bring their papers, who will guide them on board, likes to drink and that he lives off Chylonia and the ship is going to set off the next day. So I thought that maybe I can approach him, collect the documents and send him home. And this is what I did. He approaches a bit tipsy, having drank some booze. I could smell alcohol on him so I used proper communist language to get him on his feet. I collected all documents from him. I send him home to sober up. He was so glad that somebody can look the other way and send him home. Suddenly I became the person who had the students’ papers and the person bringing them on board. My heart started pounding but at the same time I believed there was no going back. I go all in.

The boarding ladder started to go up a bit, so that means that the ship is sailing off. The boarding ladder is going up. My heart is pounding. Then it stops half-way and fells down. I look left and observe the gate. It will open in a second and the Polish Border Guard will come, catch me and I am screwed. But I see that the head of the Polish Border Guard, an officer, holds Johnny Walker whiskey under his arm that he got from the old captain. He goes down, the boarding ladder goes all the way up, the tugboats are working, we can feel the engine and the propeller vibrate. The ship is sailing off. Waćka waves to me to say goodbye and I wave back at her. We are sailing off.

I had one address in Göteborg, of my English teacher who once lived in Oliwa but married a Swede and moved to Sweden. I had her address. So I thought to myself: I have to get to Göteborg because she’s rich, she married a Swede, so I have to get to her. I had her address. But I had no money. It’s five hundred kilometres away. It was the seventies so I had to pick up some girl and go to Göteborg. I see some nice Swedish girl so I talk to her. It’s all going well, she’s going to Göteborg. Wonderful. We walk out of the ferry and she asks me if I’m hungry. I say yes so she went to a booth and ordered something that today is called hot dogs. She ordered two hot dogs for us. Bröd varmkorv, this is what the Swedes call it. A bun with a korv, a sausage. And I remember there was gurksallad in Swedish and räksallad. It means that the salad had shrimps in it. Delicious. I swallowed it all in one second and it made me feel even hungrier. It turns out that she has no money left. She is a hippie. So I say to myself: “My God, now I’m in trouble”. She doesn’t want to let me go, she sticks like a leech. We walk together. She stands by the road on the freeway, sticking her thumb up. I say: if we don’t get a ride we have to walk to the stop sign and when some car stops, smile and ask if they are going in our direction. So I tell to her, and it came to me quickly: stand here and I’ll go. A BMW stops, full of girls, Swedish girls. They open a window, want to pull me inside but suddenly she appears. So they drive off. Back then nobody liked the hippies, and I had no idea about it because I was from Poland. Nobody liked when they approached them. And so we are still standing. A police car stops. They tell us to leave. In a while we managed to catch a ride, a big truck going to Göteborg. The driver was so nice and he gave us some chocolate. We are going. She doesn’t say anything to me, of course. I say to myself: it’s a disaster, but when I get to my friend Ewa I can explain everything to her and she will get rid of her. We are going, and going. I got a piece of wonderful chocolate so I feel a bit better. We reach Göteborg and he leaves us near such a beautiful bridge, just like the one in San Francisco, but white. It’s smaller in size, of course, but it’s really lovely. It’s the sunrise, the first rays of light, just like a fairy tale. Fresh air. We leave the truck. I have this address, we need a taxi. My friend is Swedish. She’s got money now. We take a taxi. It is a white Mercedes diesel. We go by taxi. The taxi takes us to the house. I call the buzzer. “Hello? Ewa? – I say – Ewa, it’s Bill. Don’t say a word, just let me in and I’ll explain everything.” She lets me in. I walk in and she can’t believe her eyes: “What are you doing here?” “Listen, give me some kronas for the taxi because the driver is waiting. I’ll explain everything.” She gives me ten kronas. I go out, pay for the taxi and the hippie follows me. “Listen, Ewa, the thing is that I escaped.

”I explain everything to her, also the situation with the hippie. She says: Get some sleep and we’ll talk in the morning.” We get up in the morning, Ewa tells me: “Listen, she didn’t sleep one wink, she was just looking at you all night.” I reply that it’s strange and that she has to send her away somehow. But I felt sorry for her because she looks like a stray dog at the door but Ewa sent her away. It’s just that I couldn’t do anything about it then, I just couldn’t. Now Ewa tells me: “Listen. My husband was a drunkard so I got divorced. I have social benefits now. I gave you my last money for the taxi. I have just jam and this knäckebröd crisp bread. It’s all I have left.”

I have to admit that when I was in Sweden, despite the fact that I felt safe, every single night I dreamt that I was back in Gdynia and that I cannot get back. The same thing happened every night. The situation got worse so I even visited doctors to get help. Every night I dreamt that I was back. I remember the first night at my brother’s house, the cicadas, hot air, and it all went away. The distance and change in climate cured me in an instant, the very first evening. Everything was all right again. I have never had such dreams any more. And so my life in Australia started.

Australians are very likeable, they are also very open. It’s not like in Europe, on the old continent, where every migrant felt unwelcome. When I was in Sweden, maybe I looked more like a Swede, with my red hair, freckles, blue eyes. But still, the moment when I started talking Swedes sensed that I am not a Swede and they didn’t welcome me as warm. With Australians it was totally different. Most of the country was built by immigrants. It didn't matter whether they were Greeks, Italians, Germans or Poles. They welcomed us heartily. It made me feel better. I felt like home from the very start. I think it was the biggest advantage. Free, large, big country. Nobody... Everyone was friendly and relaxed. Nobody had any problems with me.

Generally during Christmas season it’s really, really warm, so all those bigos, bortsch, mushroom soups are not very popular at the time but we still prepare them. We just eat very little portions. We mostly eat Italian or Greek salads. Of course, there is the traditional potato salad as well, with all ingredients cut into small pieces. This is a must. This is why we have black and red currant bushes in the garden, and gooseberry, to make compotes or preserves, to remember. Because one remembers one’s early childhood the most. And when one gets older, one tend to forget more and more what happens today but what happened when one was five or six is perfectly preserved in one’s memory. It is how it is.

How many people re-emigrate? How many people do come back? I’ll tell you the story of my brother. He ran away, left a flagship Polish vessel and after forty years decided to come back. Now my brother lives in Słupsk. He returned to his homeland, to a place where he grew up. After forty years he can go to a free country. He is a Polish citizen and he is an Australian citizen as well. He can go wherever he likes. He has a wonderful life here. He has his smells, his flavours, his flat, a white Christmas and a wonderful life. It’s just as if he has revived here. And now, a few days ago, I asked him a question: would you like to come back? “Not in a million years.” It means that the early childhood had greater impact on him than those forty years of life in Australia. So many people who have this opportunity to go to a free country, to free Poland, do come back and have wonderful lives there. And there are those just like me, who won’t come back, because they are close with their families here. I am very close with my girls. I raised them to be good Australian citizens, patriots, because that was the only way I could raise them back then. Who would want to go to a communist state? Who would have thought, back in the seventies, that the communist system will fall, along with Russia? It didn’t occur to anyone. Maybe this is why I raised my daughters to be good Australian citizens. I wanted to give them a country where they belonged. I think that many immigrants harm to their children by teaching them patriotism to a country they will never return to and, at the same time, teaching them not to like the country they live in. They are at the crossroads, they aren’t Greeks but they aren’t Australian either. They feel as if they were somewhere in between because their parents have this obsession. I didn’t do that. You are Australian, you were born in Australia, you will be Australians, love your country.

Unfortunately, back then nobody kept their passports at home, so we had to ask for permission to leave Poland and go to Australia. We couldn’t just leave for Australia, we had to travel to some neutral country first, so we pretended that we are going on holiday to France. We stayed in Vienna and we went to the Australian Embassy in Vienna. It turned out that many Poles had the same idea at the time, so we had to wait a long time. We had to spend eight months in Austria, waiting to get Australian visa but luckily, we made it. And I do mean that we were lucky because an actress is not such an attractive profession as an engineer or an architect. Fortunately, the person who interviewed us wanted cultural personalities to have... to have a chance. So, after eight months in Austria, we arrived to Australia.